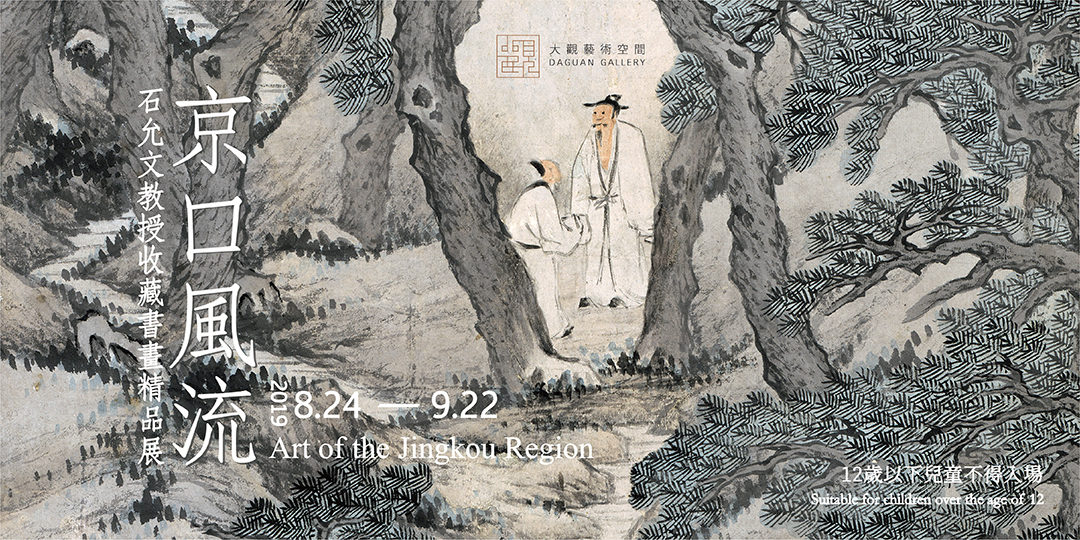

21 Aug Art of the Jingkou Region – Works from the Collection of Professor Shih Yun-Wen

Grace and Legacy of Jinjiang

Li Sijie | Editor-in-Chief, Daguan Monthly

The Jinjiang School broadly refers to a regional painting tradition that emerged during the mid-Qing dynasty, centered in the Jinjiang area—modern-day Zhenjiang. This school was shaped by a group of local painters whose work was marked by meticulous brushwork and rich, pure ink tones, often depicting the local landscapes. The movement spanned roughly from the mid-17th century to the mid-19th century.

From the late 17th to the 18th century, the so-called “Three Masters of Jingkou”—Cai Jia (1686–1779), Jiang Zhang (active during the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong reigns), and Zhang Qi (active during the Kangxi and Yongzheng periods)—represented the artistic zenith of Jinjiang painting during that era. Both Cai Jia and Jiang Zhang resided in Yangzhou and earned their livelihoods through painting, achieving renown comparable to that of Yangzhou painters.

In contrast to the Three Masters of Jingkou, who had lived in Yangzhou, Pan Gongshou (1741–1794) was a native son of Jinjiang—nurtured entirely by its culture and environment. He was mentored and supported by Wang Wenzhi (1730–1802), a scholar and cultural leader of the area, whose status as a third-ranked scholar (Tanhua) and extensive collection of art gave him considerable influence. Despite never leaving Jinjiang, Pan Gongshou gained considerable fame for his paintings. His works often bear inscriptions by Wang Wenzhi, creating harmonious pairings of painting and calligraphy. Their friendship spanned over 25 years and remains a cherished anecdote in the art world.

Zhang Yin (1761–1829), Gu Heqing (1766–?), and Pan Simu (1756–?) represent the second generation of Jinjiang painters and embody the school’s flourishing period. Zhang Yin’s paintings were known for their bold use of ink and distinctive personal style, often grounded in local topography. He deliberately adopted the aesthetics of the Ming dynasty’s Wu School, signaling a departure from the dominant orthodox style of the time. His leadership role in the Jinjiang School is evident in the number of followers he attracted—some imitated the refined precision of his early style, others the robust elegance of his middle period, but many emulated the freer, more relaxed strokes of his later works. Zhang’s own family included numerous accomplished painters—records mention over a dozen, including his eldest son Zhang Shen and the monk Mingjian, both of whom are noted in art history.

Gu Heqing is best known for his ability to capture fresh and elegant atmospheres, particularly in his depiction of light and airy scenes. Alongside Zhang Yin, he was lauded as part of the duo “Zhang’s pines and Gu’s willows,” highlighting his unique interpretation of willow trees.

Pan Simu, younger brother of Pan Gongshou by about 15 or 16 years, was active during the same period as Zhang Yin. Like many Jinjiang painters, he looked to the “Ming worthies” as his artistic models, with a particular admiration for Wen Zhengming, whose poetic elegance influenced his style. In his later years, Pan Simu adopted a more composed brush technique and used heavier ink tones.

Historically, Qing dynasty art history has largely emphasized the orthodox school. However, as academic perspectives have expanded, the dynamic and diverse nature of Qing painting has become more apparent. While the Jinjiang School was a regional movement, it offered an aesthetic distinct from the orthodox tradition and secured a meaningful place within the artistic landscape. The school’s emulation of the Ming dynasty’s Wu School carved a new artistic path. Though geographically constrained, this trend of “imitating Wu” still influenced later generations. Notably, even Tang Yifen and Dai Xi, long seen as orthodox successors of late Qing painting, maintained close ties with Jinjiang artists. Comparing changes in their styles reveals the subtle yet discernible impact of this “Wu-style revival” on the late Qing art world.